"You can't break the mirror because you don't like what you see"

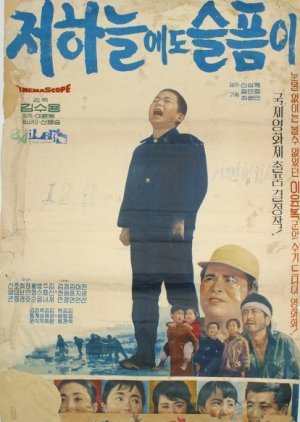

Sorrow Even Up in Heaven was based on the diary of a real 11-year-old boy whose family suffered from extreme poverty. The Diary of Yunbogi was also made into a short Japanese film by director Oshima Nagisa. Yun Bok’s story reflected the lives of many vulnerable children at the time who had no adult to rely on and had to fend for themselves in a daily fight for survival.Yun Bok attempts to attend fourth grade in elementary school when he can though he often shows up late or not at all. His mother abandoned the family and his father is a sickly gambler who assigns Yun Bok the job of primary provider for their family of five. Sister Sun helps Yun Bok sell gum on the street and in the night clubs. Younger brother Yun Sik is forced to beg for food. Fortune smiles on the children when a teacher takes an interest in Yun Bok. After reading Yun Bok’s school diaries detailing his heartbreaking struggles, Mr. Kim becomes determined to have them published.

South Korea had been hit doubly hard, first with Japan’s occupation and exploitation and then the following war that divided their country. While parts of the economy were beginning to move forward with people who had disposable income, there was also a segment of society fighting to score one meager meal a day. Through no fault of his own the survival of Yun Bok’s family rested on his tiny, narrow shoulders. He tried to stay positive and refused to resort to stealing. That didn’t mean people never took advantage of or abused him. Despite setbacks his focus remained on protecting and feeding his siblings.

SEUiH added characters who were extraordinarily selfless and kind and others completely lacking in humanity. The black and white nature of supporting characters overly simplified a complex world. The film excelled when it remembered that Yun Bok carried not only the family but the story. He was a child who missed and resented his mother, loved and despised his father. He couldn’t understand why people who had more than they could eat refused to share with those who had nothing. Even after his book was published which assured the family of food each day, the film made a point of stating that for the many other Yun Boks in Korea, there was no happy ending, no gifted source of income from heaven, only sorrow. Rather there was bone gnawing hunger that too often was ignored. Yun Bok’s story in his diary and subsequent films made from the source material reminds us that the lives behind the masks of poverty are precious and every bit as important and significant as the wealthiest man. The film never shied away from the greed and desperation of people. However, just like Yun Bok’s perseverance and resolve to take care of his family, the film never gave up on him or society as a whole.

22 June 2025

Epilogue note: From what little I could find on the real Lee Yun Bok, the money he made from his diary allowed him to finish school. He was able to go on and work in business and as a salesman. There was a possibility the family knew where Sun was working. The Diary of Yunbogi was the first Korean book published in Japan after the normalization of relations between the two countries. Disappointingly, Yun Bok did not receive royalties from the publications in Japan or their adaptations of it. Lee Yun Bok died in 1990.

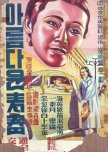

Sorrow Even Up in Heaven won the Blue Dragon Award for Best Film in 1965.

The film was considered lost until a copy with Mandarin subtitles was found in Taiwan. The damaged film was restored by the Korean Film Archive though the subtitles remain.

Was this review helpful to you?